By Dapel Zuhumnan

Contributor to THE AFRICA BAZAAR

Understanding the rise in poverty in Nigeria is one issue; understanding the forces behind the north-south poverty divide is another.

A top political leader from northern Nigerian once remarked: “In Nigeria, poverty wears a northern cap; if you are looking for a poor man, get somebody wearing a northern cap.”

That statement succinctly alludes to the economic gap and the growing inequality in Nigeria between the north and south.

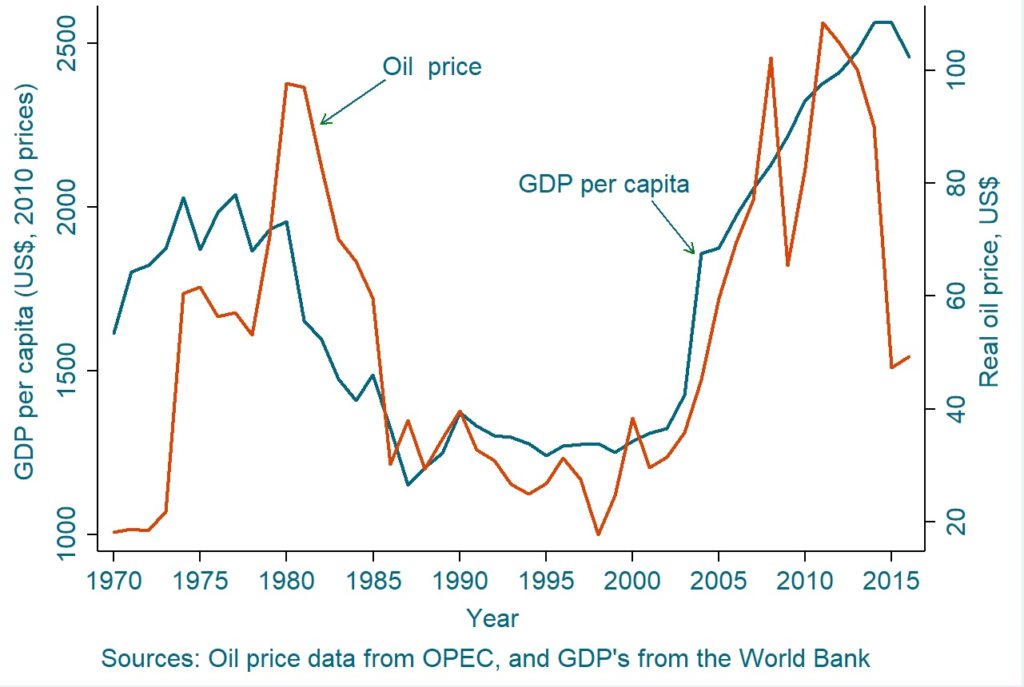

The poverty rate in Nigeria rose by 153.6 percent (or 62.76 percent if $1.25 USD/person/day 2005 PPP line is used) between 1980 and 2010, according to official figures. Similarly, the number of poor people rose to 112.47 million from 39.2 million (see Figure 1 below) during the same period. This is despite a rise in the country’s GDP per capita by roughly 19 percent and a 17.1 percent decline in the level of inequality at the time period noted earlier(measured in terms of Gini index).

So what accounts for the huge dearth gap between these two regions of the country?

Understanding the rise in poverty in the Nigeria is one issue; understanding the forces behind the north-south poverty divide is another. In this blog post, I focus on the latter and explore why poverty is so much greater in the north of Nigeria than in the south.

It’s true that much of the rise in poverty emerged from the northern part of the country. For the period that data is available, the gap in poverty between the regions opened after 1980 (see Figure 2; the difference in 1980 is so small that it is not visible when the poverty rates are approximated to two decimal places).

Figure 1: Poverty rate in Nigeria %, 1980–2010

Fig. 2: Poverty in Nigeria by region, 1980–2010

During a recent conversation about what can be done to reduce poverty in the Northern Nigeria, Florida-based professor Kyesmu Pius, who has extensive knowledge of the region’s history offered a solution. He recommends that government create an “enabling environment” that includes good infrastructural systems and programs such as good roads, security, affordable 24/7 electricity. “The North will supply the entire African continent and beyond with agricultural produce,” which in turns will produce internally generated revenue, he argued.

Before looking at this or other possible solutions, let us plough through the stylized fact on the poverty situation in both regions and, perhaps, try to understand the likely source of the disparities.

There are several factors that could account for this dichotomy.

A deeply researched empirical academic paper on the subject might reveal a more precise answer, but even such research would potentially be constrained by lack of state-level time series data—spanning decades—on development indicators and other correlates of poverty.

Instead, to better understand this dichotomy and move forward, we need a poverty index such as the one the World Bank uses in monitoring progress against poverty: An absolute poverty line of $1.25 USD per person per day (equivalent to 317.31 Naira in today’s value).

As of 2010, seven out of 10 Nigerians living in the country were considered poor based on this poverty indicator and most of the poor are located as living in the northern region of the country.

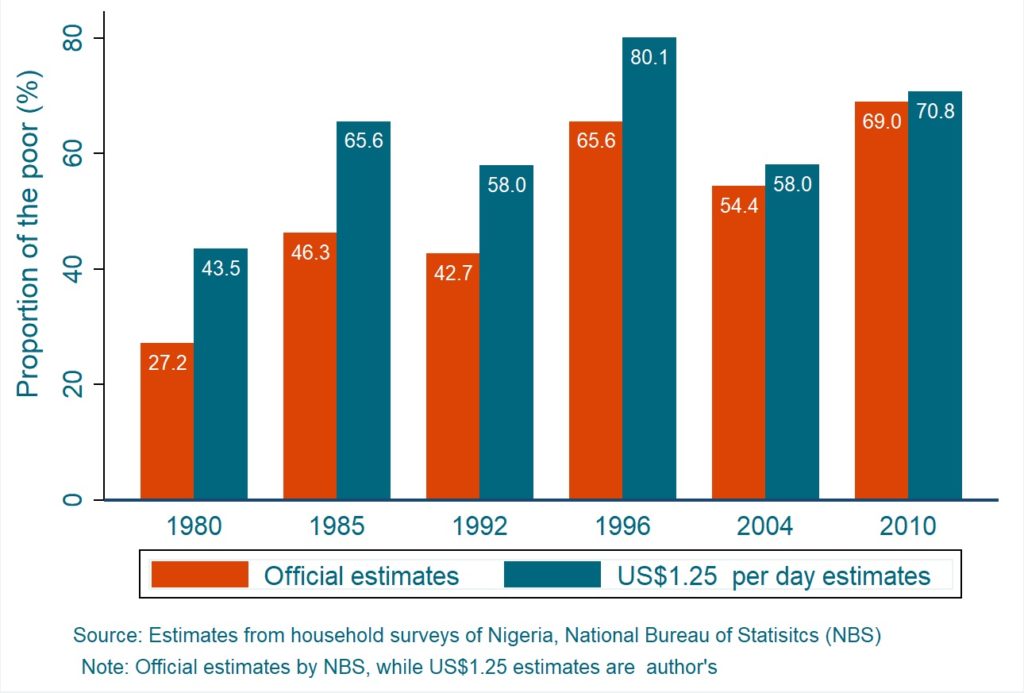

The gap between the North and South begins to show up after democracy was overturned in Nigeria, followed by the reign of three military juntas until 1999. In the 1980s, there was also a collapse in world oil price. (Evidence in Figure 3 shows that oil price and average living standards, over the past several decades, have been moving in the same direction.)

The heads of these juntas all came from the North, which means the North primarily should have benefited more from the country’s oil revenues since the military junta leaders held the reins of power in the country as well were the determining captains and players of commerce and industry.

Figure 3.Real oil price and GDP per capita in Nigeria, 1970–2016

Given this context, why then are there more poor people in the North? Or as Oxford’s David Bevan and others have argued: “Why does the South benefit more than the North?

The following are some possible explanations:

First, it could be argued that perhaps because the government, flush with oil rents, increases demand for service-sector industries in the South. But that story seems unlikely under further investigation, after all, for an extended time the North was politically dominant – which beseech another argument that If any region was going to benefit from government largesse, it would and should have been the North.

A better explanation instead has much to do with how the Northern elites used the oil revenue.

The North-South divide widened during the 1960s and 1970s, despite the political dominance of the North. The latter’s growing economic inferiority may have been at the root of the reluctance of the Northern elite to rely upon market mechanisms or to relinquish control over the distribution of oil revenue (David Bevan et al. 1999).

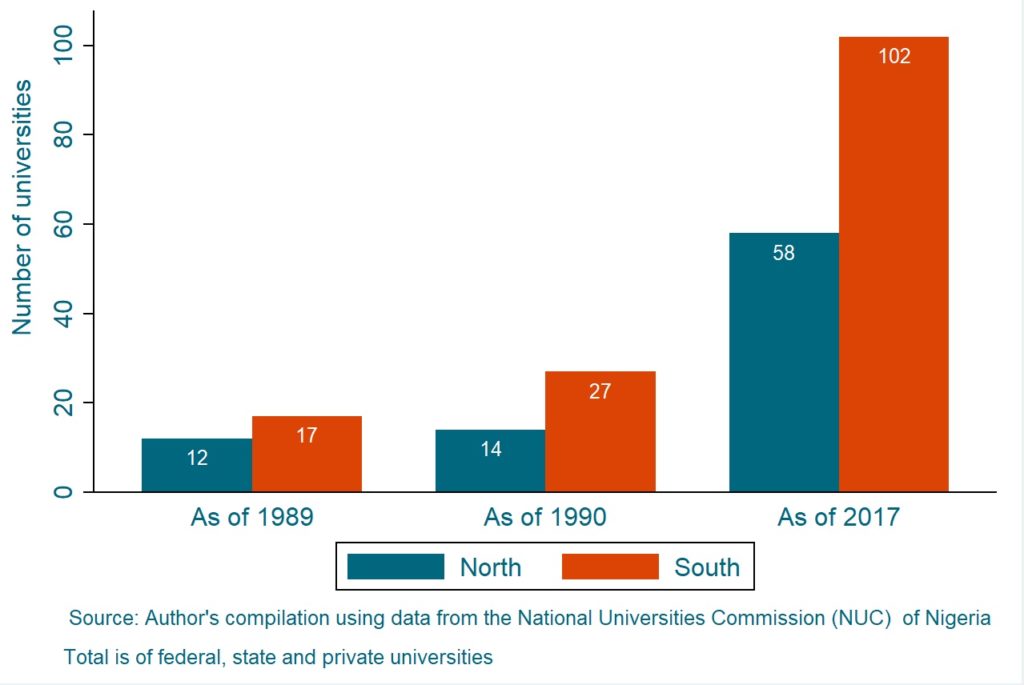

A second explanation focuses on literacy and education. Adult literacy rate is commonly recognized as key to raising living standards for the next generation. In this regard (see Figure 4), there are more universities in the South than in the North, which leaves the North at a disadvantaged. In addition, on-the ground skilled workforce that can lure investments to the region, which will help boost the economy, is currently deficient or lacking, another major disadvantaged.

In a 1999 World Bank study, Bevan, Collier, and Gunning noted a historical fact regarding education in Nigeria: The gap that already existed between the South (exposed to Western-style education through mission schools) and the North (where schooling remained largely limited to Koranic teaching) widened.

The gap in the number of universities increased after 1999 because of the proliferation of private universities in the South. There are only four private universities in the North, the rest are government-owned (it should be noted that the North is currently experiencing a drop in registration rates at colleges).

Adult literacy rate is commonly recognized as key to raising living standards for the next generation. In this regard (see Figure 4), there are more universities in the South than in the North, which leaves the North at a disadvantaged.

Figure 4. Number of universities in Nigeria as of 2017

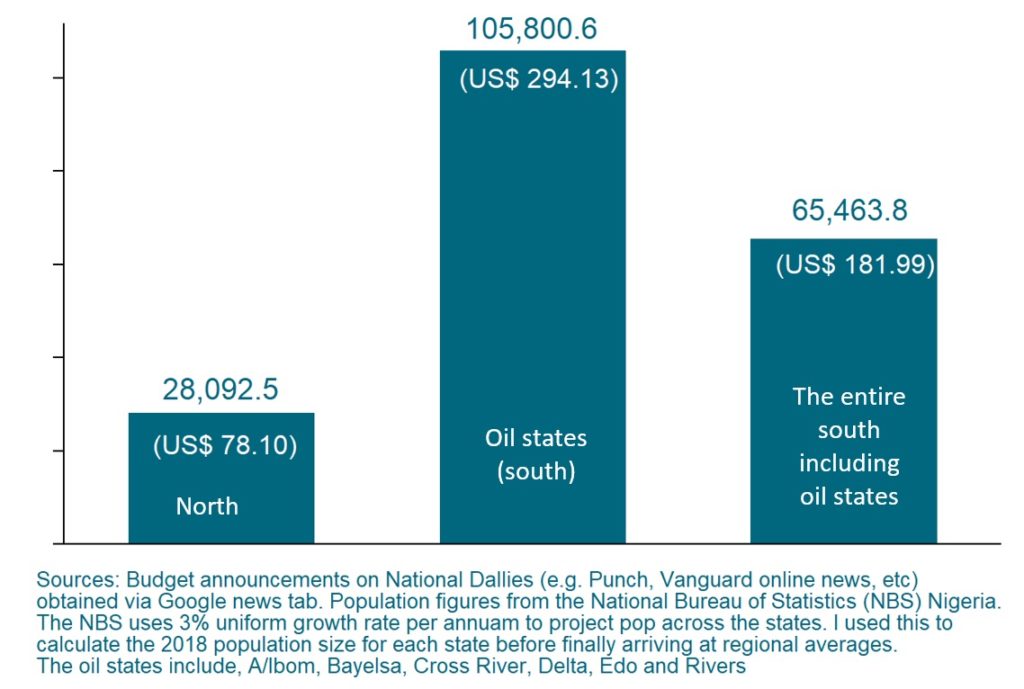

The third explanation has to do with budgeting and spending. Some would say the North tends to spend less on its citizens than the South (see Figure 5). But a closer look at the budget shows otherwise, as Chinedum Nwoko, a Nigeria-based former World Bank senior economist, and other experts have come to recognize that budgets don’t mean much in Nigeria. Instead, considering actual spending would make more sense than focusing on budgets, although that has its own set of issues. So Figure 5, below, should be viewed as a commitment to development spending, and not what leaders in these states actually spent.

Figure 5. Proposed state spending per citizen and by region, 2018

Although the North is, in terms of population size and land mass, larger than the South, the South tends to have greater availability of financial resources than the North.

For example, based on the 2017 revenue figures reported by the National Bureau of Statistics, the total revenue (i.e., internally generated + federal account allocations) in only two of 17 southern states—Rivers and Lagos—is 1.03 times the size of the combined total revenue of 14 of the 19 northern states. This could be deemed as a great source of disparity in poverty numbers across the regions as financial resources is indispensable in the fight against poverty.

An important caveat: this article does not intend to imply that the North has enormous financial resources but choses to spend less of it on its citizens, but rather is intended to serve as a comparative analysis.

No question, oil-producing states in the South receive higher monthly federal allocations (50 percent as of 1960-69; 45 percent as of 1971-75; and 13 percent from 1999-date), and also have higher IGRs than states in the North.

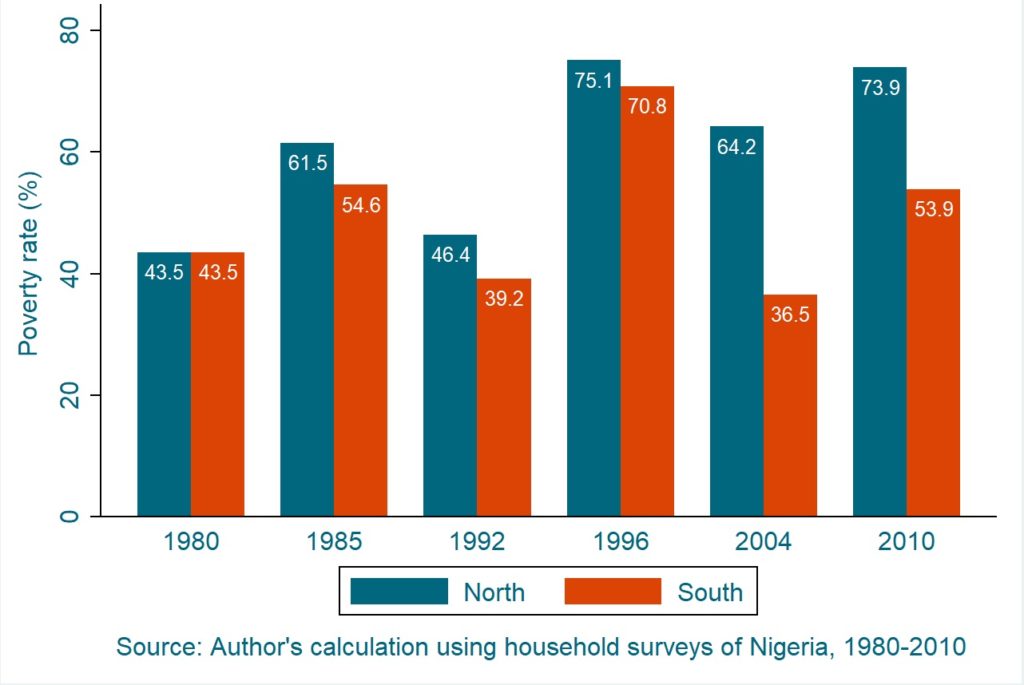

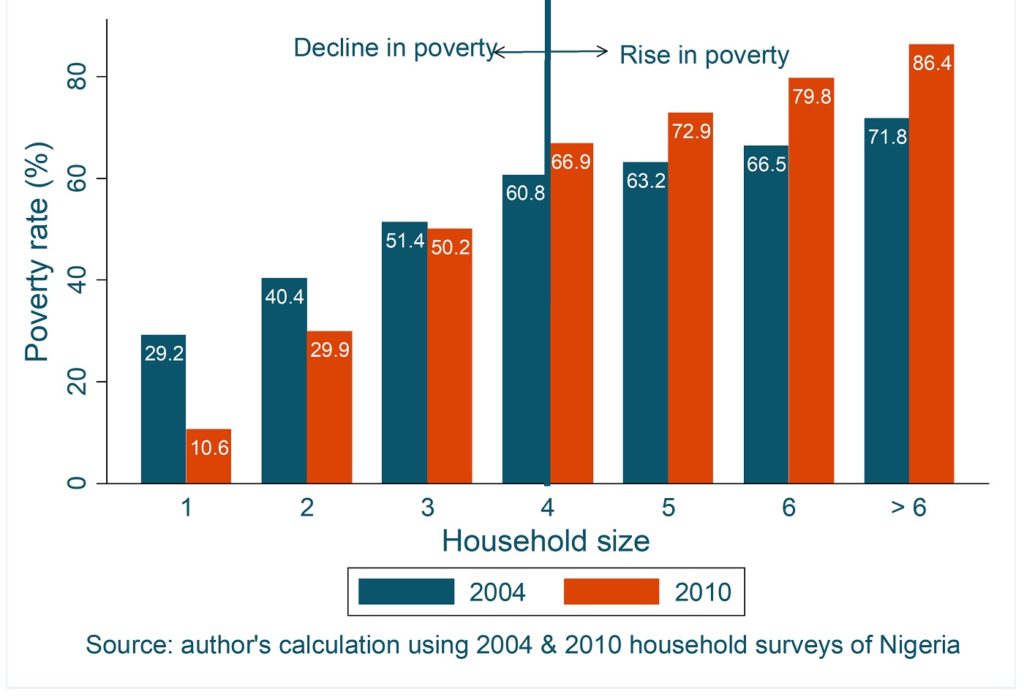

The forth and final explanation tend to do with household size. Household size is one of the big contributors to poverty in Nigeria. The North contributes more to this: Between 2004 and 2010, the poverty rate in Nigeria rose by about 22 percent (i.e., from 58.05 percent in 2004 to 70.80 percent in 2010).

As shown in Figures 6 and 7, larger households largely drove this rise. The poverty rate among households of 1-3 persons declined, but rose among households with 4+ persons.

Fig 6. (below) Larger households contribute to rise in poverty, 2004 and 2010.

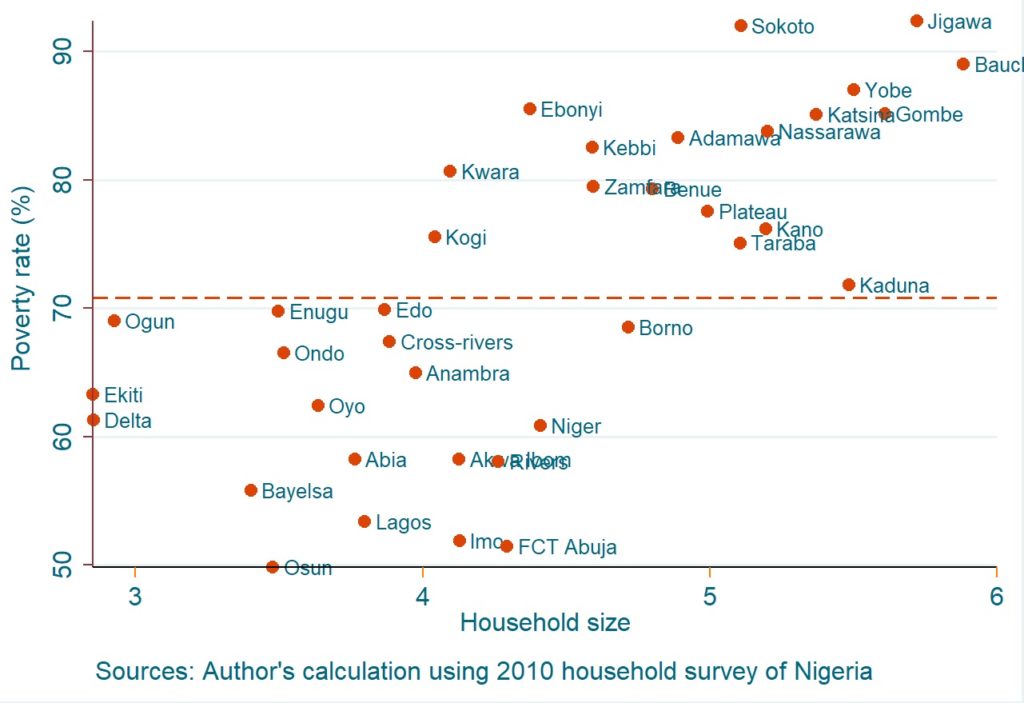

Fig 7. (above) Northern states ranked highest in poverty rate and household size

In Figure 7, the top-left and bottom-right quadrants are almost entirely empty—meaning less poverty-stricken states have smaller household sizes and vice-versa. The top-right quadrant shows states with the highest poverty rate and with the highest household size.

The Jigawa state is the top in this category. All the states here have poverty rates above the national poverty rate separated by the orange-dashed line. All the states here are from the North except Ebonyi in the Southeast.

The bottom-left quadrant shows states with the least contribution to poverty in the country as of 2010. The lowest poverty rate and lowest household size.

So what can be done?

“Government and policymakers should tap and utilize available data to address some of the issues driving poverty.”

The challenge and solutions for policymakers to close this poverty gap does not, of course, entail transferring part of the poverty from the North to the South. Instead it asks policymakers to focus on reducing the poverty in the North without raising the poverty rate in the South by focusing a greater efforts of the national government on the specific needs of the North. For example, the North has traditionally been resistant to birth control, therefore educating young girls may be the best option for addressing household size-induced poverty at the source. Data has shown that when young girls are educated, they are less likely to marry and have children at a young age.

In addition, since the North, relative to the South, lacks the financial resources required to create an environment for poverty reduction, there should be increased in federal allocations and in infrastructure funding to attract the flow of foreign investments to the region.

The ongoing instability from Boko Haram militants since 2009 continues to threaten investments flow to the region. However, there is some hope on the horizon. The current Nigerian government—headed by President Buhari, a northerner, is continuing its aggressive exploration efforts for oil in the northern region that it started a few years back. It is hopeful that the discovery of oil in commercial quantities will significantly change the fortune of those living in the region.

Lastly, the government and policymakers should tap and utilize available data to address some of these issues driving poverty. The World Bank, in collaboration with the National Bureau of Statistics, runs regular household surveys for Nigeria. This is a potentially rich source of data that could be used in the future to study and ultimately help bridge the North-South poverty divide.

Zuhumnan Dapel is a CGD-Wilson Centre joint visiting fellow from the University of Dundee Scotland.

*This article has been edited from its original for this website. The original post, first published on the CGD website, can be found there under the same headline.

© 2018 THE AFRICA BAZAAR magazine, a publication of Imek Media, LLC. All rights reserved.