In a rare interview, Malawi’s professor-turned-president reflects on his brother’s legacy, the burden of famine, and why energy is the key to unlocking the nation’s future.

Kemi Osukoya, THE AFRICA BAZAAR MAGAZINE

Updated September 24, 2025, with infographics and recent data.

Malawians have re-elected former President Peter Mutharika, placing renewed hope in the 85-year-old statesman to once again guide the nation toward a brighter future. In light of his return to office, we are republishing our exclusive interview—a compelling conversation that could serve as a blueprint for the President-elect’s vision in shaping Malawi’s next chapter

The door to the Midtown Hilton suite swung open, and instantly the atmosphere shifted. Advisers rose from their seats. A Presidential Guard snapped to attention, hand at his brow in salute. Then, with the quiet authority of a man who knows a room bends when he enters it, President Arthur Peter Mutharika of Malawi stepped inside.

He crossed the space deliberately, extending his hand across the desk where I had been waiting. His grip was firm but unhurried, his smile measured. “Your name and publication?” he asked, his voice low yet commanding.

I introduced myself, still marveling at the moment. For a journalist who six years earlier had launched the first U.S.-based industry-recognized Africa-focused business lifestyle magazine, The Africa Bazaar, which focuses exclusively on African economic affairs within the global context, with little more than vision, grit, and only a handful of staff, this was a milestone: my first interview with a sitting African Head of state

“Good,” Mutharika said, gesturing for me to sit. His aides relaxed slightly as he took his place opposite me. “Let’s get started.”

The Weight of the Room

In the Spring of 2009, when we published and distributed 10,000 printed copies of the inaugural issue of this magazine to readers in the U.S. as well as digital copies to readers in Africa, my goal was simple but ambitious: to change the narrative of Africa and its people and how their stories are being told by creating a space for a unique yet serious dialogue that interweaves the continent’s entrepreneurial spirit, innovation, economic policies, and cultures within the global landscape—something the mainstream press rarely gave justice. While the last six years have brought on some positive changes in the news coverage about Africa, they have also taught me some hard-learned lessons along the way about the African diaspora, good intentions and being misunderstood.

Now, here I was in New York City, at the height of the United Nations General Assembly, with one of Africa’s presidents across the table, ready to discuss the future of his nation.

“Is this audio?” he asked, eyeing the recorder I had just placed on the desk.

“Yes, both audio and print,” I replied.

While this is my first time interviewing a sitting African head of state, it’s not my first dance at the rodeo so to speak, interviewing a prominent business leader or High-level government officials.

I took a quick glance across the room.

The makeshift office we sat in was functional, stripped of the pomp one might expect from a presidential suite. A few files stacked neatly on the desk, aides hovering by the door, Secret Service-style security stationed discreetly outside. Mutharika explained the simplicity with characteristic pragmatism: Malawi’s parliament had recently passed a budget cutting back on nonessential travel expenses for officials—including the president himself. No lavish hotel décor, no extravagance. Just business.

That, as I would learn in the hour that followed, is quintessential Peter Mutharika: practical, professorial, and focused on building a blueprint for his country’s future.

Energy First: Powering a Nation

Our conversation began where, for him, everything begins: energy.

“You have to understand,” he said, leaning forward, “on a substantial level, nothing can be done without energy. It is our number one priority.”

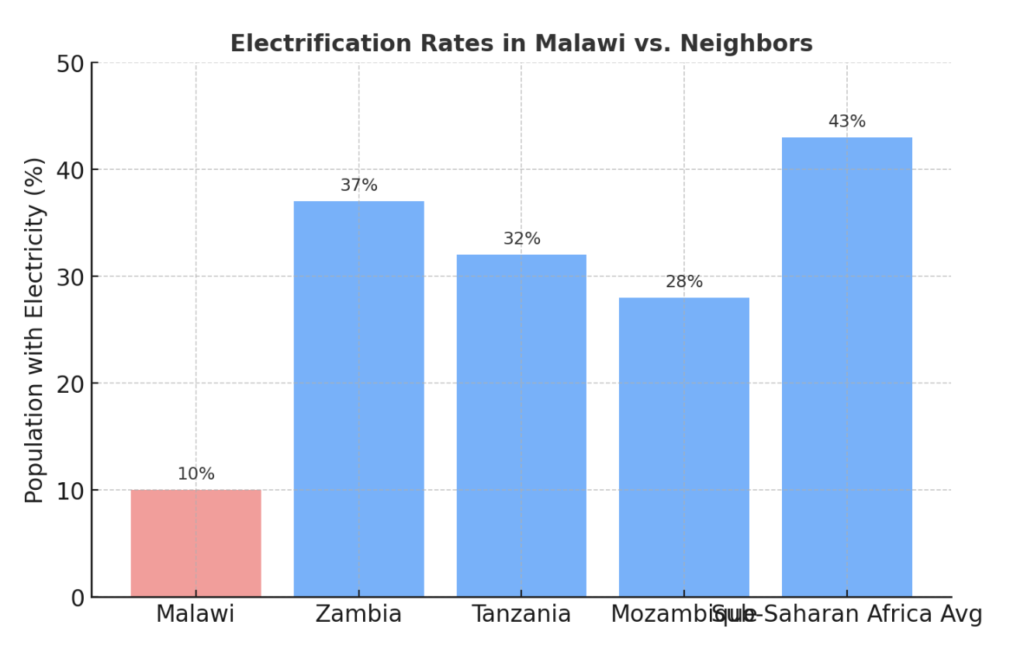

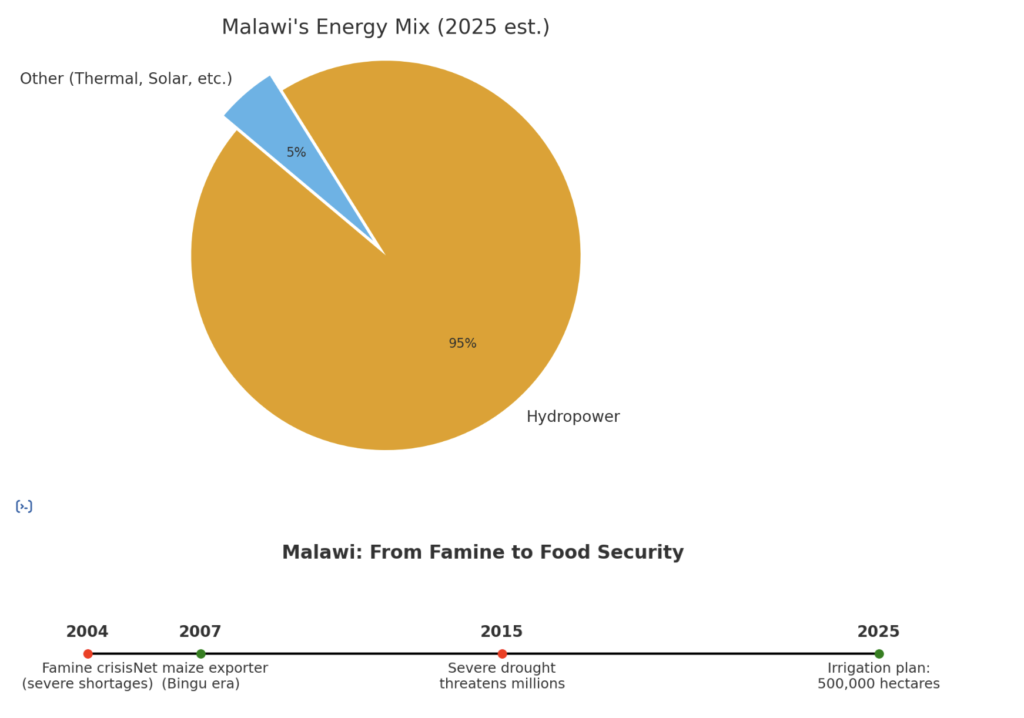

Malawi, one of the least electrified countries in the world, faces an energy crisis that touches every sector of its economy. According to the African Development Bank, only 10 percent of the population has access to electricity—37 percent in cities, just 2 percent in rural areas. The nation relies overwhelmingly on biomass energy, such as wood and wood waste, agricultural residues—which is largely used in an unsustainable manner and hydroelectric power—which drought has reduced capacity significantly, leaving Malawi vulnerable and stagnant.

Mutharika’s plan: diversify. The administration is exploring solar power, despite its high costs, and leaning into coal, which he sees as a pragmatic bridge. Neighboring Mozambique is rich in coal reserves, and he hopes to leverage that resource to expand Malawi’s energy capacity to 1,000 megawatts through partnerships like Power Africa.

Critics may bristle at coal in an era of climate change, but Mutharika is ready with a counterargument. “Coal today can be used in clean ways,” he said firmly. The byproducts, such as sulfur, he noted can be repurposed in housing construction, producing bricks more durable than mud and more resistant to flooding. “Imagine replacing fragile huts with strong, flood-proof homes,” he said. “That will change lives.”

“We are surrounded by lakes and rivers. We must stop depending on rain.”

It is not simply about powering lights; for Mutharika, energy is the foundation upon which Malawi can build mining, industry, housing, and agriculture. Without it, none of his ambitions can take root.

When I pressed if he is concerned about environmental conscious investors’ reactions to burning coal for energy, he noted there are still coal usage and coal mines in some parts of America, such as in “West Virginia and other areas like Pennsylvania where coal mining is still ongoing”

The Shadow of His Brother

Energy may be his top priority, but agriculture remains Malawi’s lifeline—and a point of personal and political inheritance.

Mutharika’s older brother, the late President Bingu wa Mutharika, presided over what many Malawians remember as a golden era. In 2004, facing famine, he defied Western donors and international financial institutions by subsidizing seed and fertilizer for smallholder farmers. The program transformed Malawi from a food-insecure nation into a net exporter of maize within a few years. By 2007, Malawi was shipping surplus grain abroad to assist other nations in crisis.

“Those were big shoes to fill,” Peter Mutharika admitted quietly. His brother’s sudden death in 2012 left both a political vacuum and a legacy to live up to.

Now, with drought once again threatening millions with hunger, the younger Mutharika is pursuing a new strategy: massive irrigation. “We are surrounded by lakes and rivers,” he said. “We must stop depending on rain.” His government has launched plans to irrigate 500,000 hectares of land across the country, creating resilience against climate volatility. “Within two or three years, we will produce enough maize to export again. We cannot let climate dictate our survival.”

Mining the Future

While agriculture anchors Malawi’s economy, mining, Mutharika believes, could propel the country’s economy forward. The discovery of uranium deposits has sparked interest, and a $30 million World Bank–EU pledge under the Mining Governance and Growth Support project, which recently produced detailed geophysical survey data mapping the country’s mineral wealth, will help improve the efficacy, transparency and sustainability of the mining sector.

“Mining requires power—lots of it. Without reliable electricity, the sector cannot take off.”

A significant milestone for the tiny Southern African nation, according to Laura Keillenberg, World Bank Country Manager for Malawi who called the launch of the airborne geophysical survey data “a game changer—proof that Malawi is serious about unlocking the full potential of its mineral wealth.”

For Mutharika, mining is not simply about revenue. It is about diversification and jobs. But again, energy looms large:

“Mining requires power—lots of it,” he said. Without reliable electricity, the sector cannot take off. Which brings him back, inevitably, to coal and solar.

| Malawi in a Glance Population: ~20 million (2025 est.) Capital: Lilongwe Languages: English, Chichewa (official), plus regional languages GDP per capita: ~USD 650 (World Bank, 2024) Poverty rate: Over 70% of the population lives under $2.15/day |

| Energy: • Only ~10% of the population has access to electricity • 37% in urban areas, just 2% in rural areas • Over 95% of current power from hydropower, vulnerable to drought |

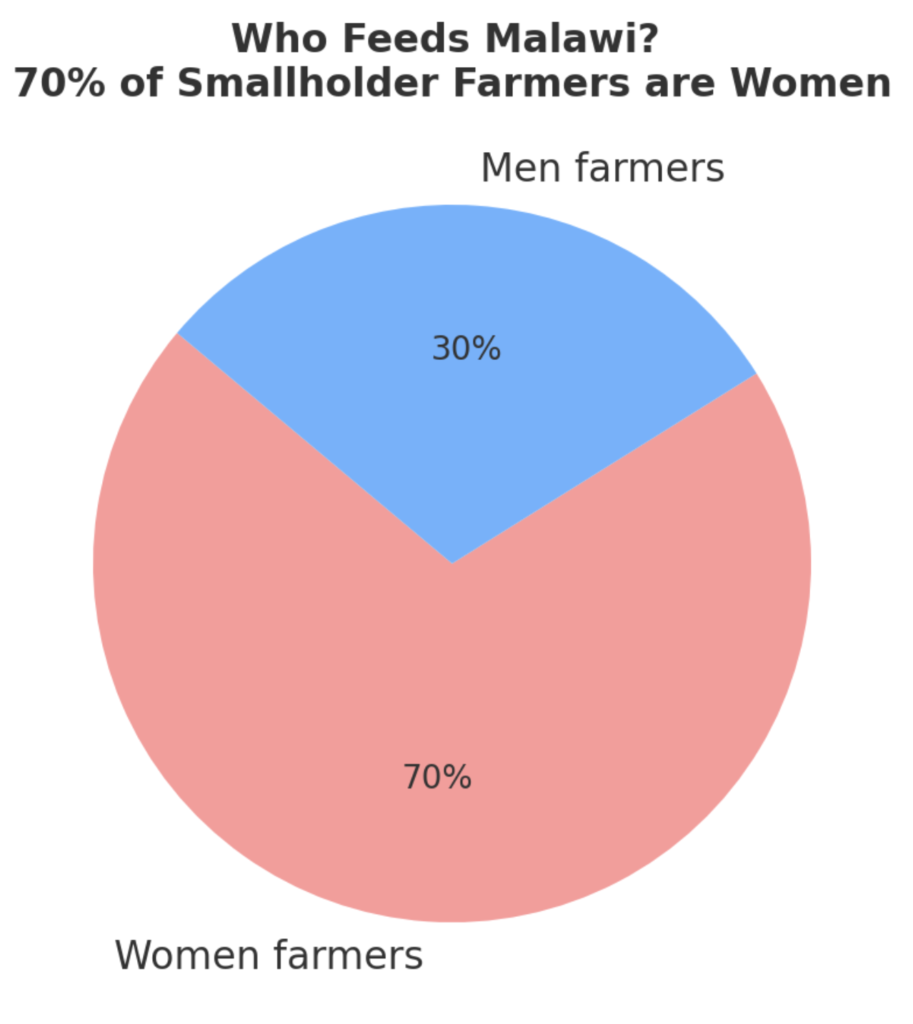

| Agriculture: • Accounts for 30% of GDP and employs ~80% of workforce • Maize is staple crop; tobacco, tea, and sugar are main exports • Smallholder farmers, many women, dominate the sector |

| Health: • HIV prevalence: ~8% of adults • “Option B+” pioneered to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission • Rising burden of noncommunicable diseases (hypertension, diabetes) |

| Education: • Literacy rate: ~65% (higher for men than women) • Gender gap persists: early marriage, teen pregnancy, and lack of facilities limit girls’ schooling • New initiatives aim to provide hostels and sanitation for girls, plus return-to-school programs for young mothers |

| Key Challenges: • Low energy access • Climate-driven food insecurity • Infrastructure deficits • Gender inequality |

| Opportunities: Expanding energy mix (solar, coal, hydro) • Large-scale irrigation projects • Growing interest in mining and natural resources • Regional trade and investment partnerships |

Housing with Dignity

One of the more striking elements of our conversation was Mutharika’s passion for housing. He described mud huts collapsing in floods, families torn apart by the AIDS epidemic, and children left to raise siblings alone.

“Girls must have the same chance as boys.”

His administration has launched a program to subsidize cement and coal-ash bricks, enabling families to build sturdier homes. For the poorest—elderly citizens, people with disabilities, households headed by orphans—the government builds homes outright.

“These children, a whole generation orphaned by AIDS, are left in charge of their siblings,” Mutharika said, his voice heavy with empathy. “Those we build houses for free.”

It is housing as both social policy and economic stimulus, tied again to energy, industry, and dignity.

Health and Education: Investing in People

When I asked about Malawi’s greatest challenges beyond energy and food, Mutharika did not hesitate: health and education.

On health, he pointed to progress in stemming HIV transmission from mother to child through the “Option B+” program, which has made Malawi a model in sub-Saharan Africa. His next goal: universal treatment access under the Vancouver Declaration. But he is equally concerned about noncommunicable diseases like diabetes and hypertension, often undiagnosed in rural communities. Mobile clinics, preventive education, and new medical schools are part of his plan.

AFFILIATE PARTNER’S PRODUCT: You have nutrition gaps. Grüns fills them. From gut health to energy and brain health, these modern gummies have been carefully formulated with 60 potent ingredients to revive and transform the whole body vitality with critical nutrients that Grüns covers. Check out the link

Save up to 52% on Gruns the most comprehensive green gummies.

Education, particularly for girls, is equally urgent. “Violence against girls is a real barrier,” he admitted. Long walks to school expose them to harassment. The absence of sanitation facilities forces many out of classrooms once they reach puberty. His administration is building hostels and toilets for girls, and allowing young mothers to return to school after childbirth—a progressive step in a region where pregnancy has often meant the end of education.

“Girls must have the same chance as boys,” he said simply.

Women in Leadership

On the political front, Mutharika acknowledged Malawi still has far to go. Female representation in parliament dropped sharply in recent years, and his cabinet has fewer women than he would like. He pointed to Rwanda’s constitutional quota system as a possible model. “What Rwanda has done in integrating women into politics and parliament is wonderful,” he said. For now, he has appointed women to several ambassadorial posts in key countries, including in South Africa, Egypt, Zimbabwe, but he sees this as only a beginning.

“Gender equality – that is one of the things I was discussing with some people over here (he was referring to the U.N General Assembly discussions)- that maybe we need to develop an affirmative policy like the one that was done in Rwanda‘s Constitution, that certain constituency, only women can compete in that area. The problem for African political leaders like him, he acknowledged is how best choose, and reach women.

Trade, Investment, and the Global Stage

No national blueprint can succeed in isolation. Mutharika is actively courting foreign investors from Asia, Europe, and the United States. Indian financing has already supported a new sugar factory near Lake Malawi, while American agencies like OPIC have signaled interest in microfinance programs for smallholder farmers.

Behind Malawi’s agricultural backbone are women—who comprise the majority of smallholder farmers. Women make up 70% of Malawi’s smallholder farmers but often lack financing and land rights.

The Peter Mutharika Administration is developing cooperative models and a commodity exchange to ensure they receive fair prices for crops. “At the moment, traders pay almost nothing,” Mutharika explained. “But when farmers can bring their crops to a commodity exchange where buyers compete, they will get a better price. That will change livelihoods.”

The Professor President’s blueprint for a new Malawi

What struck me most during our interview was not only Mutharika’s policy agenda but his demeanor. Before politics, he spent decades in the United States as a law professor, unable to return home during Malawi’s turbulent years. That academic grounding shows in his methodical explanations, his insistence on connecting policy dots, his willingness to reason through a question even when aides are signaling for him to wrap up.

Unlike leaders who inherit ossified systems, Mutharika sees himself as a builder. “This is a chance to design a new plan from scratch,” he told me, his eyes steady.

As our time drew to a close, his press secretary gestured again for the interview to end. Mutharika waved him off until he finished answering my final question about girls’ education. Only then did he rise.

He extended his hand once more, thanked me for the conversation, and instructed his aide to give me his personal contact card. “If you need more information, reach me,” he said.

Walking out of that hotel room, I carried more than notes on a recorder. I carried a sense of a leader intent on blueprinting his country’s future from the ground up—energy to agriculture, housing to health, gender to governance.

In an era when many leaders seem consumed by optics, Peter Mutharika projected something rarer: the quiet determination of a man trying to lay foundations.

And in Malawi, a country too often overlooked on the world stage, those foundations may make all the difference.

*This Interview has been updated with infographics and data. The original interview was conducted in October 2015 and was first published in the December 2015/January 2016 issue. The online version has been updated.*

© Copyright 2025 Imek Media, LLC.