It took a long time for this memorial to be created and it will stand for a longer time [as a reminder ] of our commitment to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020,” New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio.

Kemi Osukoya

December 2016

Corrine Schneider has lived in New York city for over 50 years and remembers very well when AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) ravaged her Greenwich Village neighborhood as well as other neighborhoods and cities across the United States, including San Francisco during the 1980s and 90s, taking many young lives. It was a time when fear, ignorance, bigotry and homophobia reigned supreme and permeated the country as well as the rest of the world, holding humanism captive.

“It was a sad period. So many young [people] died,” Ms. Schneider recalls painfully on a recent Thursday morning. “I used to see couples walking down the streets and one of them would be thin, and just holding on to each other just to be able to walk and just those memories of that period and how sad it was that the society turned its back on them because of who they were.”

On a clear blue-sky, mild weather December morning, thirty-five years after the AIDS epidemic ravaged New York city, hundreds of people, including Ms. Schneider, gathered at a small triangular shaped Park located across the street from Lenox Health Greenwich Village in lower Manhattan for a ceremony marking World AIDS Day and to unveil a AIDS Memorial in tributes to victims and survivors of the AIDS epidemic.

Ms. Schneider, 91, who uses a four wheel walker for mobility and standing, said for months she watched from her apartment window as the Memorial site was being developed and built, so when she read a few days ago in the local community newsletter that an unveiling ceremony would take place on December 1 to honor victims and families whose lives have been impacted by HIV/AIDS, she knew she wanted to attend the event to pay tribute.

On the day of the ceremony, she woke up early, did her daily morning routine, dressed up and began her slow walk from her home to the ceremony site.

“Seeing a memorial sculpture [in the neighborhood] commemorates their lives just acknowledges how blind society was to what was going on and not just blind, they knew what was going on. But because the people who were involved and getting sick, and who were dying were people they didn’t consider human, almost,” Schneider, who worked for Planned Parenthood for over 30 years until her retirement, recalled. and says she feels bittersweet that a AIDS Memorial is finally being dedicated to honor and acknowledge those who died during the epidemic..

“I think things are better now generally in the world,” says Ms. Schneider as she stands inside the Memorial space. “But this is a good reminder that we should always pay attention to what’s going on and if we can personally as a voter or whatever, try to do something to make it better- make the society better,” she adds.

“I think this event serves as an example of how [we] think the Memorial and the park really carved out the first public space in New York city that’s dedicated to the AIDS epidemic,” Christopher Tapper, cofounder of the New York City AIDS Memorial, tells The Africa Bazaar. “Our hope is that the site continues to be something that brings the community together and when there are important events, like finding a vaccine or the death of someone from the disease – they would now have a place to go because previously there’s the Stonewall, which was kind of a place for Lesbians Gay Bisexual and Transgender in New York city, where people would go gather but anything really to relate to the AIDS epidemic, there really wasn’t a place to gather.”

Ensconced at the former home of St. Vincent Hospital – ( St. Vincent was the ground Zero site of the AIDS epidemic in New York state at the time) – in Greenwich Village, in Manhattan, the New York City AIDS Memorial, an elaborate translucent origami-shaped steel tent sculpture, stands perpendicularly to Lenox Hill Emergency Hospital. The sculpture, designed by Brooklyn-based architect firm, Studio ai, is meant to serve as a Living Memorial – a space that brings community and people that have been affected by HIV/AIDS to share experiences of grief and loss as well as personal stories that will bring more awareness and understanding about the disease or to learn what that period what like living in the neighborhood and in New York city.

“We didn’t want to give one meaning to it, there are many meanings and layers and everyone can come in from their own personal experience,”

“When they started the competition for the memorial, it wasn’t just let’s do a competition or memorial – it’s a living memorial because [AIDS] is not something that’s in the past. It’s still going on,” says Mazeo Paiva, one of the principal architects at the firm. “So it was important to create a place where people can experience grief – have a personal space to experience what happened to them when they lose somebody like a family or a friend to the [disease] or for the people living in the city to understand what [the memorial] was about – sort of a room where you can step in.”

So how do you create a physical tribute that honors the victims as well as provide a gateway for people to learn and share experience?

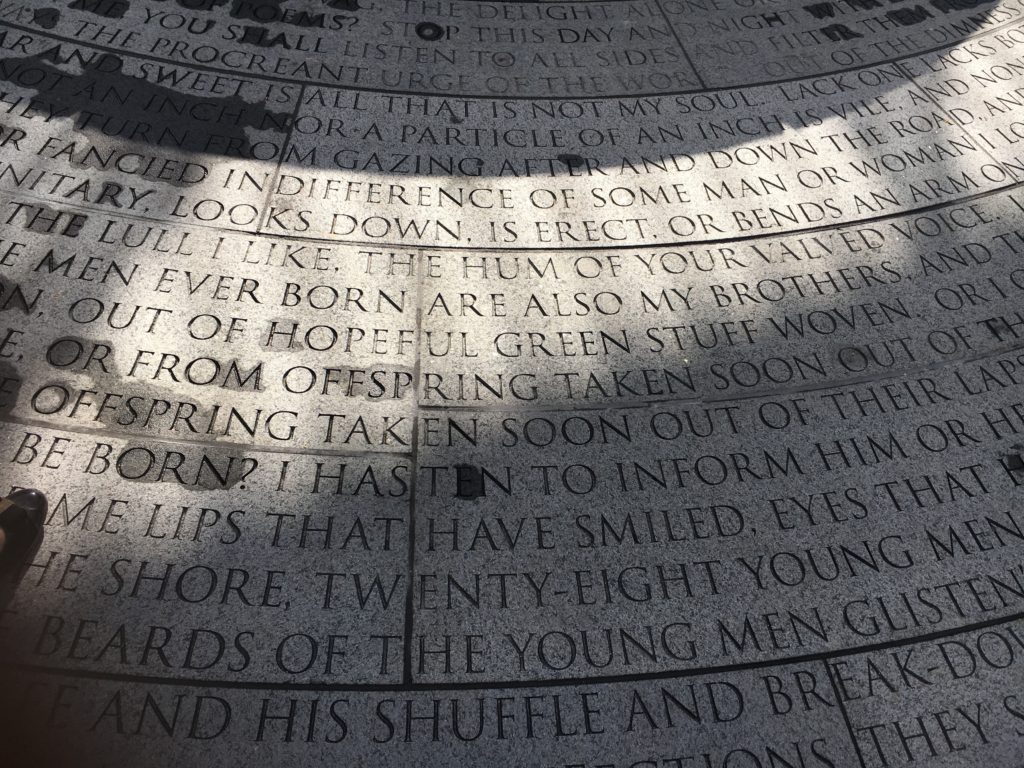

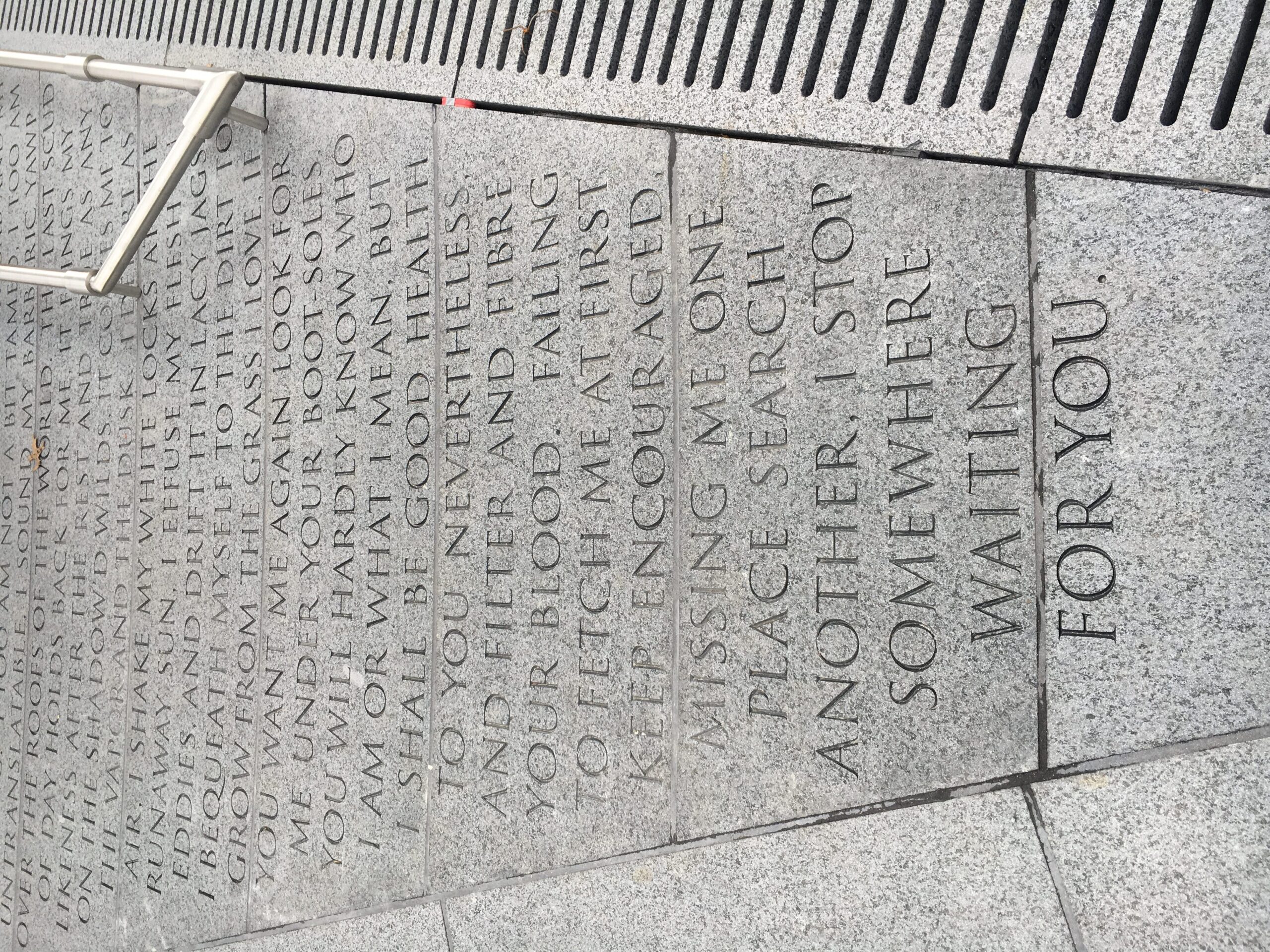

Paiva and his colleagues at the firm, keeping in mind the city’s landscape, designed the main part of the Memorial to blend seamlessly with the neighborhood and at the same time provides a sanctuary so when someone walks on the sidewalks and steps into the park and the Memorial space,- which is defined by the steel structure- there are featured elements – such as a water fountain at the center that symbolizes the geographic location of the neighborhood as the epicenter of the AIDS epidemic- that immediately resonate as well as define the place as sacrosanct. On the memorial ground surface are several granite paving stones containing etched words that are displayed ostentatiously in circle surrounding the fountain and across the entire memorial space. In this context, the designer took inspiration from the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington D.C., where names of soldiers were etched on the walls.

A closer inspection of the words, which initially look like juxtaposed random words, reveal the syntax of a poetry. They are nine thousand etched words taken from Walt Whitman’s poem “Song of Myself.”

What is unique about the ground surface being covered with etched words instead of names is that when a person first glances across the floor to read the words, their eyes may serendipitously connect with a word, which may has an instant effect and its own meaning, making it more significance to the person. Adding to this fortuity is the play of light as it reflects through the sculpture’s triangular patterns on the etched granite stones to create distinctive silhouettes that simultaneously evoke and capture the apparition effect of the New York City AIDS Memorial.

The reflection of the sculpture on the water fountain also intensifies the uniqueness of this experience, which is exactly what the designers and founders had in mind.

To fully experience the content of Walt Whitman’s poem, it is best to start at the apex of the fountain and walk counterclockwise surrounding the fountain until the path narrows into a triangle at the peak of the park.

“We didn’t want to give one meaning to it, there are many meanings and layers and everyone can come in from their own personal experience, people can take their kids – maybe they will discover something new when they are reading the words,” says Paiva. “We feel that sometimes people don’t really understand that [epidemic] period- what it really was- I think some people believed that it was already cured.”

Are We There Yet?

“One of the reasons the disease still rages on is because of stigma, which have clouded the perception that AIDS is a gay disease”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, globally, an estimated 36.7 million people are living with HIV/AIDS, and each year 1 million people die from AIDS-related causes, and 2.1 million people become newly infected by HIV. Two-third of new HIV infections worldwide occur in sub-Saharan Africa.

The United Nations AIDS Program Coordinating Board recently adopted a new strategy to end the AIDS epidemic as a public threat by 2030.

So far, more than 35 million people have died from the disease. There’s 1.2 million Americans living with HIV/AIDS and many of them lives in New York city, according to city health officials.

The AIDS epidemic was one of the most destructive pandemics in New York’s history and the country. During that period, New York lost thousands of people to the disease, a number that federal, state, city and local government officials and non governmental organization activists are all working to make sure it never happen again.

Through the New York AIDS Institute, which was established by Governor Mario Cuomo in response to the epidemic, the state gained access to new research and new knowledge that have helped it reduce the number of new HIV/AIDS cases over the last decade by 40 percent and have gone from diagnosing 50,000 people a year to 3000 people a year.

Federal and states funded research programs and initiatives like President’s Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief have also made it possible for HIV positive individuals like Eric Sawyer to continue to live and work as a highly contributing member of the society.

Sawyer, who is gay and a New Yorker, witnessed and experience himself the devastation and stigma of AIDS, and the stigma associated with being gay 35 years ago. Now, he and several people worry that the incoming Trump administration could reverse the progresses that the society has made collectively on the HIV/AIDS medical front and acceptance of LGBT people.

“Back then, we didn’t have acceptance as LGBT people,” Sawyer tells The Africa Bazaar during an interview. “There were a lot of people who died alone in that hospital whose family abandoned them when they found out they were gay and they have AIDS.”

Sawyer’s partner died from the disease in the late 1980s.

Things have changed since then. Now, people are a lot more understanding and acceptance of homosexuality and cognizant about the HIV/AIDS disease and treatments.

Held each year since 1988, people and businesses on December 1 pay tributes on World AIDS Day in solidarity and support of victims, and survivors of the disease. The day serves as a reminder to improve education, raise awareness and money for research to end the disease.

“The epidemic has been unsuccessful now because of the medicalization of the response. At the beginning, we only had prevention as medication to stop the spread and because we didn’t know how to treat it and we don’t have a cure yet- however, now we have effective treatment that can keep people like myself living and functioning as a contributing member of the society 35 years after I became symptomatic,” Sawyer explains.

One of the reasons the disease still rages on is because of stigma, which have clouded the perception that AIDS is a gay disease, says Sawyer, especially in the developing world where being diagnosed with HIV/AIDS is still associated to those early cases amongst gay men in America and Europe,. During the 80s and 90s AIDS epidemic, a lot of early cases in the U.S. and Europe were also among drug users and prostitutes.

This unnecessary association of the disease to a specific group is why many people do not get tested for the disease or seek treatments in places like Africa, where there are high cases of heterosexual HIV transmission, because they are afraid they would be deemed homosexual or a prostitute. For example, if a married man with kids tested positive for HIV, he would be regarded as homosexual and if an unmarried woman tested positive, she would be labeled a prostitute; a married woman who has HIV is deemed to have been unfaithful to her husband.

When such situations occur, people living in cities where there are access to free medications and treatments funded by the PEPFAR program or Global Fund usually retreat in their shame and by choice die in the shadow than to admit or possibly be discovered to have the disease, and to deal with the stigma associated with it, which also present a huge public health challenge and threat.

The New York state government recognized this early on as a public health threat and took positive steps – such as funding AIDS research and educational programs to bring awareness. They established a needle exchange programs within communities, which have significantly helped reduce the number of intravenous drug infection, make getting tested for HIV simpler and easier by allowing registered nurses to screen patients for the diseases, and changed the law to broaden the number of people who can take HIV test starting by age 13 years old and older.

The government recently recommit addition funds to funding AIDS research and education to end the disease by 2020.

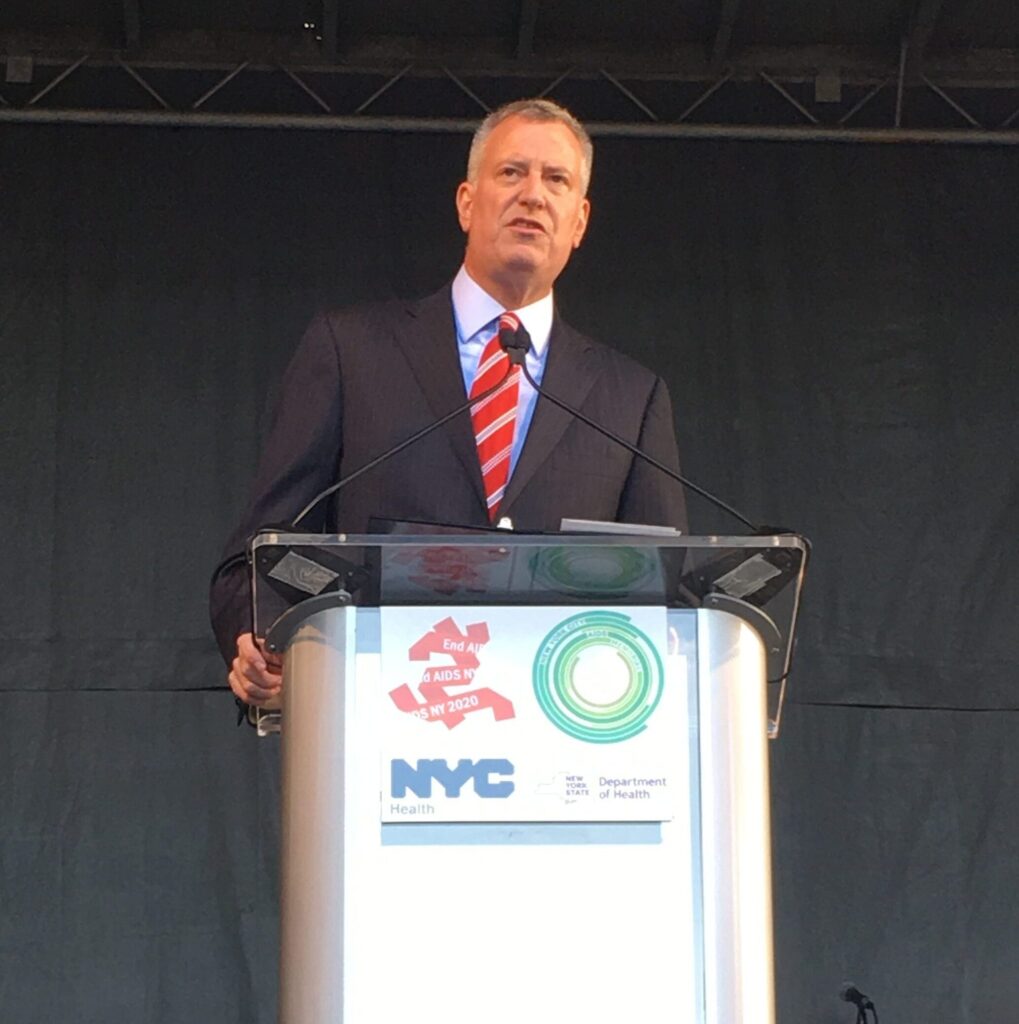

New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio speaking at the unveiling of the New York City AIDS Memorial reiterates the government’s commitment to create “a future without HIV/AIDS.”

“I remember the early days of this epidemic, the confusion in the city. New York city was pushed back on its heel, back on its back and activists fought back, doctors fought back,” remarks Mayor De Blasio during his speech. “It makes me sad to think of the loss but it makes me proud to know of the courage and the fight we’re waging today. It took a long time for this memorial to be created and it will stand for a longer time but it must remind us of the goal we set to achieve and end to the AIDS epidemic by 2020 and let this be a place where we recommit ourselves.”

Right now, New York State is on the cusp of eradicating mother to child HIV transmission, which dropped significantly since 2014 to zero in September of this year.

Uncertain Future

While several progresses have been made globally on HIV/AIDS medical treatments, on removing the stigma and the acceptance of people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, the pledge to eradicate the disease by 2030 might not be enough to assure some people and HIV survivors in America like Michael Borden that the incoming Trump administration would not turn its back on HIV survivors and cut funding for AIDS research and treatments.

“It’s scary what happened in the 80s. It is scary and I’m afraid now for our country that it might happen again,” says Mr. Borden, 65, a former resident of Chelsea during the AIDS epidemic who now lives in San Francisco and volunteers at a AIDS hospice. “The animosity towards gay people and lack of funding for federal research during Regan presidency in the 1980s because of what they thought was a gay or drug users and prostitutes’ disease – and now I wonder what might happen now that we have elected Trump as president. How many people might die because we have people running our country who don’t have basic human values,” he notes emphatically.

Mr. Borden, who is in town for a scheduled business seminar and takes the opportunity to attend the unveiling of the AIDS Memorial, has kept apprise on the progress of his former Chelsea neighborhood, including the development of the memorial.

“On the medical front, we have made huge progress, certainly on HIV treatments. I’m a person living with the disease, I take pills two times a day and I feel great,” he discloses. “But on the socioeconomic front, we have taken a huge step backward. What does it says of St. Vincent that had more than 100 years of tradition serving everyone in New York, including people who couldn’t paid to being replaced by multimillion dollar condos,” he asks rhetorically.

Waiting for Time to Heal Pain

It is often said that time heals all wounds. However, for some of the survivors AIDS and people who witnessed the epidemic, time has neither erased nor healed the raw instinctive emotional pains that come along with losing a loved one or close friends.

For Edward Dunne and David Ralston, a married gay couple, it’s a painful reminder of friends that were lost to the disease.

“We have the experience in the 80s of coming here everyday – to St. Vincent [Hospital]- to watch our friends die,” says 73 years-old Mr. Dunne tearfully, pausing briefly before continuing. “Does a memorial do anything – it reminds people and that’s important because the Village was really devastated. Most of the gay men in the city lived here in Chelsea- a huge percentage- we lost a huge percentage of our friends – over 35 friends died to the disease.”

“It’s a very painful thing when you think about the number of people that died and how little was done for them at the time and now [the city] makes amends for it by honoring the dead. We loss them,” says 81 years old Mr. Ralston in a tone that conveys he’s still displeased at what happened to his friends. “It was done like in many cases because of political reasons.”

A Focus on Courage

For Philip Calkins, 63, who lived through the epidemic and lost more than 15 friends to the disease, it is appropriate to have the New York City AIDS Memorial built at the site. Like Ms. Schneider, he has watched the memorial get built. While he was eager to attend the unveiling in honor of the AIDS victims, visiting the memorial for the first time brings up unexpected ambivalent of emotions as he remembers his friends who died.

“The impact to the art community and broadway was dark. The loss was tremendous,” he recalls as we walk our way through the small park toward the inside open space of the AIDS Memorial. “I have lived in the neighborhood for 38 years. When I moved here, it was the gay ghetto – there were gay-owned and operated bars, restaurants and stores and then I watched the neighborhood disappeared one by one. You know you walk to the subway and see the same people, and then you weren’t seeing those people anymore – the devastation was a daily thing.”

He pauses briefly before continuing to speak as his eyes glance quickly across the space and become transfixed upon the water fountain for a a few minutes. “I lost friends – 15, then I made new friends and lost them too,” he says without taking his eyes off the fountain.

“I’m seeing people that I haven’t seen in a long time, and that good, but I don’t think today is a particular good day to experience [what the AIDS Memorial means]” he answers cryptically in response to one of my questions. “But the impact – I have my moments at home,” he adds.

He tells me that he is starting a new tradition this year in remembrance of the friends he lost. He has on a military-lookalike black Scottish kilts, a black teeshirt and a jean jacket along with a black hat that has a red and white checkered-piece of cloth attached to it, in symbolic of the red ribbon wore by people on Worlds AIDS Day.

“I felt it was a way to be respectful and to mourn those that lost the battle against the disease,” explains Calkins. “I want to focus on their courage.”

That bravery – their strengths and tenacities that push through the veneer of hate, violence against gay men and women, discrimination in housing, in the workplace – is the reason why someone like New York City Councilman Corey Johnson, who found out in 2004 that he is HIV positive, is able to find acceptance within the LGBT community, his family, and even consider running for a public office.

“Being someone who was born in 1982 and found out I was HIV positive in 2004, I would literally not be alive today if it were not for the tens of thousands of activists who fought for us,” says Johnson. “Let’s this memorial reminds us that every men, women and child lost to this disease have a life that was valuable and meaningful and beautiful and they will never be forgotten. And also to remind us of those heroes who rushed to those in need and didn’t walk away.”

Family versus Faith, A Mother’s Choice

Long before there was acceptance, there was ignorance. And not only ignorance of the science of the disease or homosexuality, but ignorance of each other.

Until recently, most people in the society were uncomfortable with homosexuality. Most people didn’t want to talk about homosexuality, so most of the society hid from it, and collectively adopted a “better to avoid it than to confront it” attitude, even when they witnessed discrimination and violence acts against gay men and women, including in housing, and in the workplace.

Sometimes, religious dogma further perpetuates these prejudice and resistance. These feelings, often held by both straight as well as gay people, are used to justify bigotry and discrimination against other people.

God created everybody and he knows what he’s doing, so why should there be a difference in the way we look at things and why can’t we love people the way God loves people for who they are?”

In the 1990s when comedian Ellen DeGeneres came out to the public that she is gay, there was a huge backlash against her that ended her television acting career for nearly a decade because people were afraid of gays and didn’t understand homosexuality at that period.

While lately there has been more acceptance of LGBT people by most societies, there is still some prejudice and resistance from religious groups toward gay people, which often ultimately can hinder a family acceptance of their loved ones homosexual identity, leading to self denial, ostracizing and sometimes a person suicides.

For some people and their family, religious dogma creates an emotional struggle between faith and family.

Mrs Kelterborn knows and understands what it means to wrestle spiritually due to the Church doctrines.

Her son, Paul Kelterborn is one of the cofounders of the New York City AIDS Memorial. Paul and his cofounders Christopher Tepper and Keith Fox conceived the idea to build the memorial when Tapper, who read David Frances’s book “How to Survive a Plague” brought up the idea to honor the 1980s AIDS victims.

Paul, who does not have HIV, was born and lived in the midwest until the early 2000s. He grew up in a Catholic family and always knew he’s gay, but never disclosed his sexuality to his parents until 2002 after he graduated from college.

“When Paul told us he is gay – he had known for a long time and his siblings all knew, he is one of six – his dad and I didn’t know,” explains Mrs Kelterborn. “Living in the midwest at the time, the idea of being gay was not acceptable and having to process that as a parent – when he told us, I’m not going to pretend that it was an easy thing initially – but it was like, he’s my son and I’m going to love him no matter what. But we had to go through a process with it. We had to talk it through.”

Mrs Kelterborn first sought spiritual guidance and understanding from her Catholicism beliefs but quickly found out as it became an hindrance that presented her with what was irrefutably a divisive choice, one that asked her to choose between her love for her child and family or her faith.

What helped Mrs Kelterborn and family get through that period was the family unity and the great love they have for each another.

“I don’t know any one thing that made me accepted it, it was just the love within our family,” she says. “I don’t know if my faith helped me that much because being a Catholic- I think that hindered it more than anything and made me struggle more – but just the fact that – as a parent the most important thing to me is my kids – if that’s who he was then that’s who he was.”

Finding that acceptance and support has brought the family closer than ever before. Mrs Kelterborn and some of Paul’s siblings and nephews were at the unveiling of the AIDS Memorial to show their support.

Like any mother, Mrs Kelterborn is extremely proud of her son and what he has accomplished, especially with the AIDS Memorial.

“As a mother, I’m really proud. The fact that he conceived it and followed through and made it happened,” she says delightfully. “It’s a real treasure for the city to acknowledge all the people, and not only the people that died from AIDS, but also the people that worked with them. I’m an healthcare professional and I’m aware of it but I haven’t seen it to the extent that it occurred here and I just think it’s wonderful that this group made [the memorial] happened. It’s a place that people can come in to meditate.”

For her, meditating and finding spiritual solace in her faith, which she still practices occasionally, is an ongoing struggle, especially given the resistance against the LGBT community from some religious groups.

“I’m still struggling [with my faith] to this day. I go back and forth all the time about where I want to be with that because people who are gay – it’s not different – they are just people. Paul is Paul, the same person as he was before he told me he is gay. You know you just have to love people for who they are,” says Mrs. Kelterborn.

“I still go to church and there are moments when I think – like when I found out the percentage of Catholic that voted for Donald Trump, – I asked myself why I’m still a part of this?” she says as she continues to explains her ongoing struggles with the Church doctrines. “But there is something that I get from just being Catholic- not the dogma or the church beliefs – there is just something that I get spiritually, but I also question it all the time. Why do I still continue to participate in something, an organization that discriminates against my own child? I don’t believe that God – I mean God created everybody and he knows what he’s doing, so why should there be a difference in the way we look at things and why can’t we love people the way God loves people for who they are?”

That is a question that the world would continue to ponder for generations to come.

© 2016 THEAFRICABAZAAR magazine, a publication of Imek Media, LLC. All rights reserved.