The Quiet Rise of Africa in a $200 Billion Coffee Economy

Kemi Osukoya | Markets & Inside Africa

After half a decade of droughts, heat waves, and climate whiplash, coffee farmers across East Africa are daring to feel optimistic again. From the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro to the highlands of Ethiopia and the fertile zones of Uganda and Kenya, the 2024–25 harvest is shaping up as a modest but meaningful recovery—one that is increasingly central to the global coffee market’s fragile balance.

In Tanzania’s Kilimanjaro region, coffee trees are heavy with maturing cherries, their branches greener than they have been in years. Farmers describe a season that is not perfect, but workable—an important distinction after recent cycles that saw output collapse to a quarter of normal levels. Climate change has not spared the region, but its effects have been uneven. While Brazil, Vietnam, and much of Central America have battled drought and extreme heat, parts of East Africa have faced the opposite problem: too much rain. Last year rainfall in some Tanzanian districts doubled, disrupting flowering and harvest cycles. This season, precipitation remains above average, but by a manageable margin, allowing crops to develop.

That resilience matters far beyond local communities. Global coffee markets had been counting on East Africa to deliver a rebound of two to three million bags to offset weather-driven losses elsewhere. Much of that hope has rested on Uganda, Africa’s second-largest producer, where the government has thrown its weight behind expansion. Kampala’s Coffee Roadmap aims to lift national output to 20 million bags between 2025 and 2030 by replanting aging trees, expanding cultivated areas, and distributing millions of seedlings. Progress has been uneven—access to inputs and finance remains a constraint—but momentum is building.

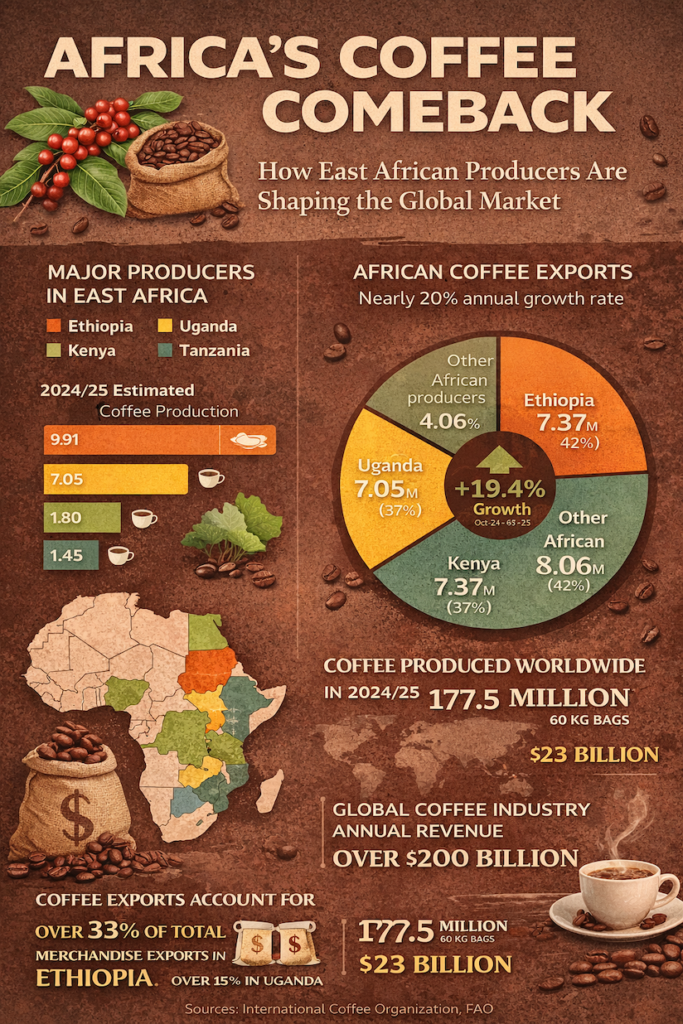

The numbers tell the story. According to the International Coffee Organization, Africa exported 1.73 million bags in October 2025, up nearly 22 percent from a year earlier. The continent closed the 2024–25 coffee year having shipped 19.69 million bags, the third-highest volume on record. Ethiopia and Uganda led the surge, each posting record exports of 7.37 million and 8.26 million bags respectively, supported by strong harvests, elevated global prices, and the release of accumulated stocks. Their combined shipments in October alone jumped almost 29 percent year-on-year.

This is not a one-off. Africa’s share of global coffee exports has been quietly rising, now around 14 percent, even as South America’s dominance has slipped and Asia—driven by Vietnam and Indonesia—has surged. Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi are no longer peripheral suppliers; they are increasingly price-setters at the margin, particularly in Arabica and higher-quality Robusta segments. Producer prices reflect that shift. In 2024, farm-gate prices rose nearly 18 percent in Ethiopia and more than 12 percent in Kenya, offering rare relief to growers squeezed by years of volatility.

Coffee’s economic weight makes the rebound consequential. The crop supports roughly 25 million farmers worldwide and underpins foreign-exchange earnings for some of Africa’s most vulnerable economies. In Ethiopia, Burundi, and Uganda, coffee accounts for a significant share of merchandise exports and finances a large portion of food imports.

Globally, coffee production is valued at about $23 billion, trade exceeds $26 billion, and the broader industry generates more than $200 billion in annual revenue. Europe and the United States remain the largest consuming markets, but demand growth is increasingly coming from Asia and Africa, where instant and at-home consumption is rising even as café culture plateaus in parts of Europe.

Prices remain elevated. Coffee surged nearly 39 percent in 2024, according to the latest data, driven by supply disruptions in Brazil and elsewhere, and could rise again if weather shocks return. Demand is famously inelastic—drinkers rarely quit—and supply responds slowly because coffee is a perennial crop. That combination produces sharp, persistent price swings. Shipping costs, tariffs, and logistics disruptions only amplify the effect, shaping how international prices filter back to farmers.

Yet beneath the surface, the market is rebalancing. Global production reached about 177.5 million bags in 2024–25, slightly ahead of consumption, creating a thin surplus that masks low inventories and ongoing climate risk. Arabica’s share of exports has edged lower as Robusta gains ground, reflecting changing tastes and the growing role of instant coffee in emerging markets. Green beans still dominate exports, but soluble coffee’s share is rising, signaling shifts in consumption patterns.

AFFILIATE PARTNER BRAND

Policy support is now as critical as rainfall. The African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) program, currently passing through U.S. Congress for a three year renewal, not only offers East African coffee exporters duty-free access to the U.S., bolstering margins and incentivizing investment in processing, logistics, and quality improvements, it is a lever for industrialization, financial inclusion, and long-term market positioning that could stabilize revenue streams, encourage private sector investment, and deepen regional integration, while a lapse could erode competitiveness against Latin American and Asian producers.

For East Africa, the implications are strategic. Governments and cooperatives in Ethiopia and Uganda are pushing not just for volume, but for value—better quality, traceability, and deeper links to fast-growing markets in the Middle East and Asia. Saudi Arabia, where coffee consumption is booming, has emerged as a new focal point for African exporters, with business forums and trade missions underscoring the sector’s diplomatic as well as commercial pull.

As 2026 unfolds, coffee prices are expected to remain volatile, buffeted by rising demand, fragile supply, and intensifying climate pressures, yet African producers are no longer on the margins—they are increasingly at the center, quietly fueling the world’s coffee habit, one harvest at a time.

Coffee is no longer just a crop—it’s a high-stakes global circuit where Kilimanjaro rains, Brazilian droughts, Red Sea freight, and Shanghai cravings all converge to set the price of your morning cup, from New York to Nairobi.