By Kemi Osukoya

THE AFRICA BAZAAR MAGAZINE

* March 2015

ART REVIEW:

In early 2000s, Kehinde Wiley was doing his artist-in-residence at the Studio Museum of Harlem after obtaining his MFA from Yale in 2001. One day, while walking on the street of Harlem, he came upon a piece of paper with an image – it was a police mugshot of a young black man. He picked it up and looked at it. That mugshot became a catalyst for his work.

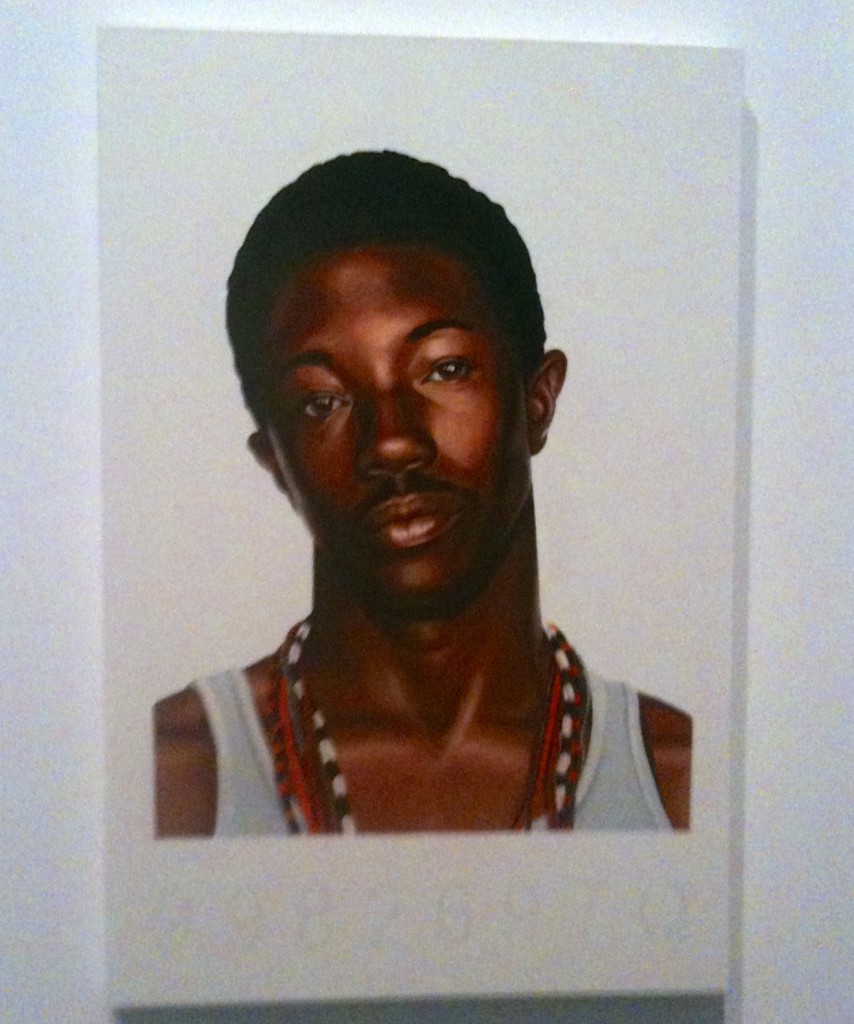

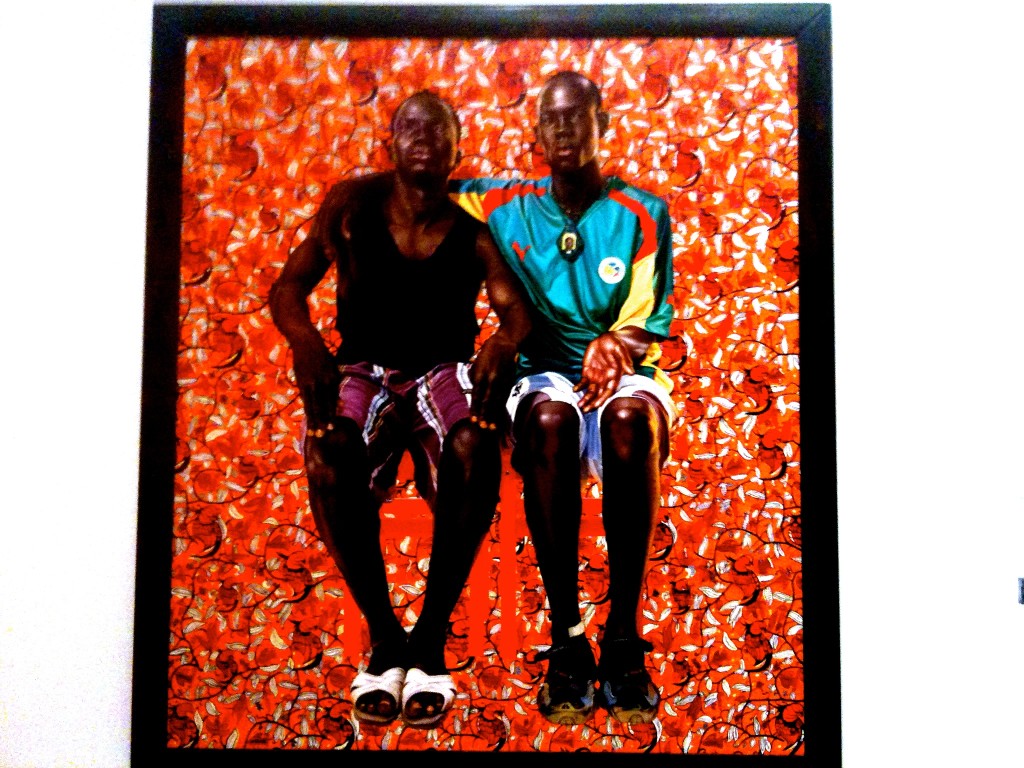

Few black artists have successfully juxtaposed and oscillated classical and contemporary art as Wiley has. You could say his work is flamboyant and labeled it ornamental, whichever way you may end up describing it, boring is not a label that’s associated with his work because however different each portrait or sculpture is from the next, there’s a signature- a luxuriant humanity to his art, which speaks to his obsessive perfectionism of his vision.

And like many great artists with vision, Wiley has made art that are fundamentally illusionary but at the same time conveys all the authenticity in the context of a real world that’s very familiar to most people.

Much like the American television drama series, Empire, starring Terrance Howard and Taraji P. Henson, or Andy Warhol’s artworks, Wiley’s work is pop culture-infused, but also based on stereotypes – racial epithets. No detail is too small. Every stroke is meticulously placed for maximum effect.

Flamboyant, ostentatious, fancy, and using combination of details both historically verifiable and racial emblem, his subjects are removed from the grimace realities that people too often associate them with, and instead are placed in poignant contexts of power– spun-off of classical European portraitures- to convey the fundamental risky misrepresentation of race, sexuality, and class in today’s world and the invisibility of blacks in classical European art.

Using a somewhat visual narrative stratagem to highlight Mr. Wiley’s work, curators of Contemporary Art at the Brooklyn Museum have put together a sixty objects show, “A New Republic,” the artist’s first museum survey, currently on view at the museum through May 24, comprising of striking portraits of African-American men- from his early portraits paintings that was inspired by his observation of street life in Harlem as well as new, unexpected, and less familiar work, and his recent forage in stained glass and sculpture.

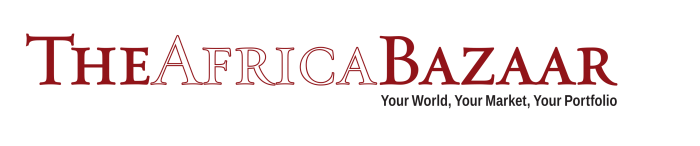

Among the objects and portraits that visitors will see in the Rotunda when they step off the museum’s elevators on the fifth floor to see Mr. Wiley’s work is a bronze bust sculpture titled, “Houdon Paul-Loius, 2011.” The intricately carved bust image of an African-American male with a meticulously folded cloak around his neck; has an uncanny accuracy to Roman Emperors and warriors bust sculptures – the like of Julius Caesar – that museumgoers who are familiar with art from the ancient Roman Empire would immediately recognize.

The sculpture, acquired last year by the museum ahead of the exhibition, will especially resonate with American museumgoers today, calling to mind the racial stereotypes of urban young black men and the recent events around the country – the recent shootings of unarmed young black teens and men in America.

Viewers’ attentions are quickly drawn to focus on the details and spectacle before them and as such, the cloak around the bust’s neck now mirrors an urban street wear, “a hoodie.” The head and facial expressions – head tilted sideways in a urban, hip-hop youth swag style-as if asking what? What are you looking at?,” could embody a combination of beauty, masculinity and confidence that seems to stem from high level of self confidence, strength and power. Or, it directly affirms society’s racial suspicious phenomenon that’s too often associated with black men’s expressions- arrogance, anger and fear inducing.

Unlike the Roman emperors busts that symbolize strength and power, Wiley’s busts leave room for individual’s interpretations and at the same time tactfully point to the society’s suspicions of black men: Here, black men wearing hoodies [hoodie in a way has become like a cloak for black men] symbolize brutal strength, which may induce fear in other race.

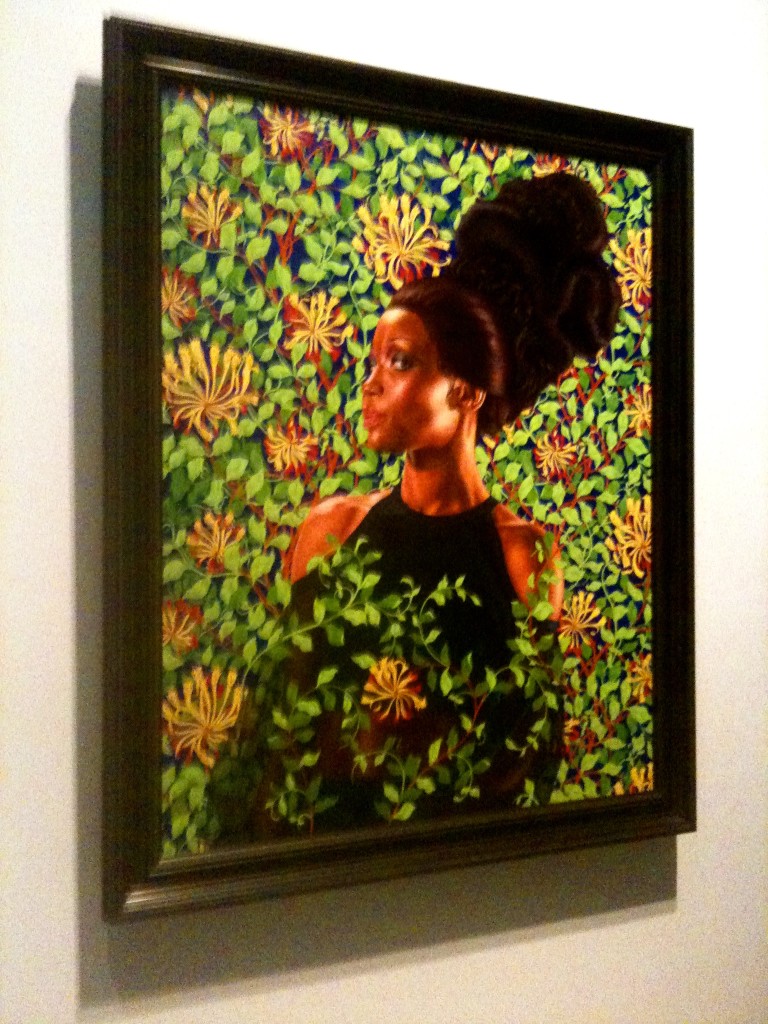

The concept of beauty and the symbolism of hair and hairstyles as representations of societies, cultures and identities are some of the issues that Mr.Wiley also explored in his other art pieces. For example, his first woman sculpture, titled “Bound, 2014,” Mr. Wiley once again opts for the ostentatious over restraint to create a voluminous hair-style so sumptuous it looks less like a hair and more like a twisted beautiful tree that serves to make a powerful and autonomy rich symbolic value.

In most societies and cultures, hair, especially women’s hair is symbolic with strength and beauty. This is especially significance for both genders in the black community during the civil right movement when wearing an Afro-hair-style was emblem of political empowerment, beauty and pride.

All of Mr. Wiley’s art pieces included in this show convey not just meticulously composed strokes and shamelessly decadently luxes, its also packed with allegory incidents- a world that is subject to tensions that exits entirely outside of the portraits.

There’s an unspoken dialect in each portrait and object – a slightly pedantic quality of high level public service that I like which invites viewers in to try to remedy the historical and cultural narratives and at the same time schools them in the art of understanding of what it means to be invisible or misrepresented in a society.

This show creates a sort of mindful dialogue that we as society too often like to sweep under the rug- a contemporary conversation dealing with the obvious yet often ignored steaming volcanic tensions in our world, as results of historical invisibility, of economic and racial inequality- upping our attention to the pending imperiled quotient that awaits our world.

There are feelings of awe, recognition, inclusiveness yet ambivalence that make looking at the objects and the subjects in the portraits in an unusual but illuminating angle, stripped of stereotypical epithets or labels that have been assigned to them, wielding their beauty in a specific, coded way that reveal absolute humanity.

The sixty objects on view at the museum are not just dazzling and graceful, they are skillfully mastered arts engineered as corrective remedy to our incomplete cultural narrative and the historical invisibility that some people in our society feels.

*The review is republished this month in honor and celebration of the Black History Month in the U.S.

Copyright © 2015 ImeK Media, LLC. All rights reserved.