Kemi Osukoya | Markets & Policy

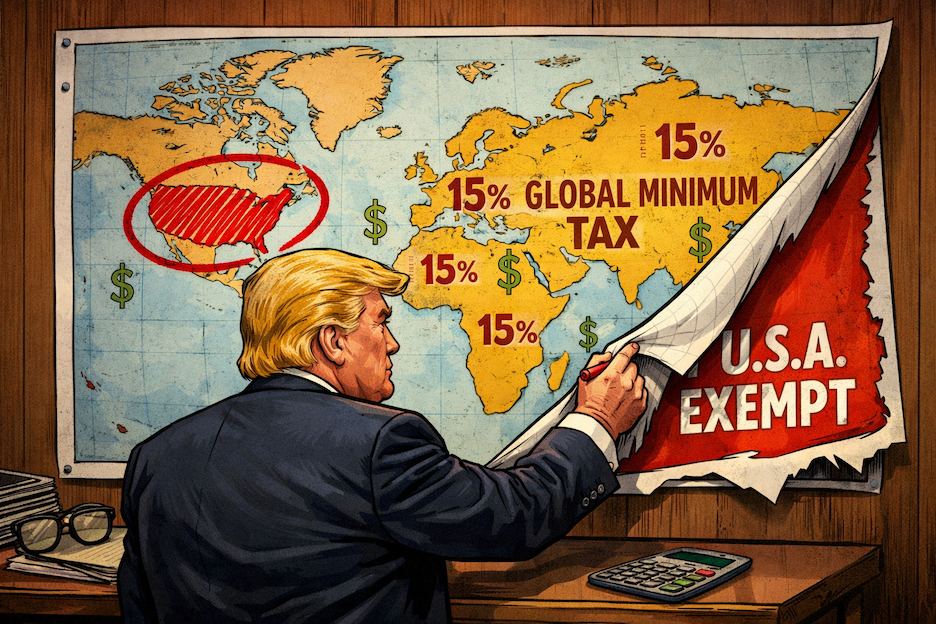

The U.S. Treasury has secured an agreement with more than 145 countries under the OECD–G20 framework that exempts U.S.-headquartered companies from the global minimum tax known as Pillar Two, allowing them to remain subject only to U.S. minimum tax rules.

The move delivers on President Donald Trump’s day-one Executive Order declaring that the Biden-era OECD deal would have “no force or effect” in the United States, and it marks a decisive assertion of American tax sovereignty over multinational profits.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent in a statement on Monday described the agreement as a victory for U.S. workers, innovation, and competitiveness. The deal preserves the value of U.S. research-and-development credits and domestic investment incentives, while shielding American companies from what Washington views as extraterritorial taxation. In practical terms, it means U.S. multinationals will not face the 15% global minimum tax applied to their European, Asian, and emerging-market rivals—even as most of the world moves ahead with implementation.

For African economies, the implications are complex and consequential.

The OECD’s global tax framework was designed to curb profit shifting and stabilize revenues by ensuring large multinationals pay a baseline level of tax wherever they operate. Pillar Two relies on coordinated enforcement: if a company pays too little tax in one jurisdiction, another country can apply a “top-up” tax. But the U.S. exemption weakens that architecture. Without reciprocal enforcement from the world’s largest capital exporter, the system’s effectiveness—particularly in developing economies—comes under strain.

Disclosure: THEAFRICABAZAAR may earn a commission at no additional cost to readers if you buy a product from our Affiliate partner

American firms operating across Africa now gain a structural advantage. With higher after-tax profits and fewer global constraints, U.S. multinationals may expand more aggressively in sectors ranging from technology and pharmaceuticals to agribusiness, mining, and financial services. For African governments eager to attract capital, this may look like a short-term win. But it comes with a fiscal cost.

Countries such as Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa risk collecting less corporate tax than anticipated under Pillar Two, especially where enforcement depends on cooperation from a firm’s home jurisdiction. If U.S. parent companies are exempt from top-up taxes, African tax authorities may struggle to capture their fair share—either through legal challenges, complex transfer pricing structures, or simple asymmetry in enforcement power.

The exemption also sharpens competitive pressures within Africa itself. To retain or attract U.S. investment, governments may feel compelled to extend tax holidays, special economic zones, or sector-specific incentives—reviving the very “race to the bottom” the global minimum tax was meant to end. In oil, fintech, manufacturing, and digital services, policymakers could find themselves trading long-term revenue for short-term capital inflows.

There is also a geopolitical dimension. European and Asian firms bound by the OECD rules may find themselves at a disadvantage in African markets, facing higher effective tax rates than their U.S. competitors. Over time, this could distort competition, reshape investment flows, and tilt market share toward American companies—not because they are more productive, but because they are more lightly taxed.

Supporters of the global tax deal argue that developing countries still benefit from greater transparency and more stable tax bases. Yet many African governments have long pushed for a more inclusive, UN-led tax framework that better reflects their needs. The U.S. exemption reinforces those concerns, highlighting how global rules can fracture when major powers opt out.

The Treasury says it will continue engaging with foreign governments to ensure stability and advance discussions on digital taxation. But for Africa, the lesson is already clear: global tax policy is not just a technical exercise—it is a competitive battleground.

As Washington protects its multinationals, African economies will need sharper coordination, stronger transfer-pricing enforcement, and smarter incentive reform to avoid losing ground. In a world of uneven rules, sovereignty cuts both ways—and the cost of exemption may be paid far from Washington.